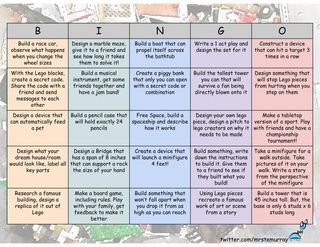

"How It's Done: Remote STEAM Learning with LEGO Education Bingo Boards

Educators and parents can support remote STEAM learning through LEGO Education Bingo Boards

Where: Lexington Public Schools, Lexington, MA

What: Creating LEGO Education Bingo Boards to help educators and parents teach STEAM at home

As schools across the country began to close in response to COVID-19, my first thought, like thousands of other teachers across the world, was, “How can I supplement my teaching so my students can continue to learn during these unusual times.” You see, I’m a middle school STEM teacher, which means I’m used to providing my students with hands-on, tactical projects. I’m used to pushing my students to build robots, having my students work in groups and build together. How was I going to continue pushing my students to get hands-on and think like an engineer while they were at home?

Not all students have access to computers, but it’s still important they continue to have hands-on projects, just like in the classroom, to keep them engaged and excited. I connected with our 6th grade math teacher to think through ways for educators –- and parents -– to continue teaching STEAM skills at home in a fun, interactive way.

Before schools closed, we just started using the new LEGO Education SPIKE Prime kits in our classroom to get students learning STEAM skills through hands-on learning. It was a great tool because it provided low-floor, high-ceiling tasks such as the Hopper Race, in which you design prototypes to find the most effective way to move a robot without wheels, to more difficult projects such as Design for Someone, in which students could stretch their STEAM skills by trying to solve real-world problems.

Read more: LEGO Education Spike Prime In-School Review from Tech & Learning

I wanted to replicate the same hands-on and low-floor, high-ceiling experience for all my students -- and students around the world. Something that allows students feel confident in the projects they were completing at home.When looking at the way SPIKE Prime lessons are set up, you’ll see that basic instructions are provided, but students are encouraged to use their creativity to make their own unique creations by placing the bricks differently or writing a different code. I wanted to bring that approach to remote STEAM learning, ..."

Read the full article at its source: https://www.techlearning.com/how-to/how-its-done-remote-steam-learning-with-lego-bingo-boards?utm_source=Selligent&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=16780&utm_content=T%26L+Remote+Learning+4%2F17%2F20+&utm_term=1272672&m_i=_ybcXjkbG0le6X3CEbbRUm_FtkzAyJbTPF0a0rhKFfy5gHYJD80KVs3UcVKiCRb97Q78KS2RBW1cC3dmn3gLcaiON1unqNr__V&M_BT=810043649812